As regular readers know, this blog software will only recognize one author for each article, either Robin or me. However, this post was coauthored by me and our sons Burke and Ryan. The only way I can credit them is by this introductory statement. Thanks, guys!

—————-

Robin was on second base when the batter smacked a sharp line drive past the shortstop into left field. Off at the crack of the bat, she had clear sailing into third base. What she did not expect was the third base coach – her husband — windmilling his right arm signaling her to round third and head for home. She lowered her head and tried to pick up the pace. Unfortunately, speed was not in her skill set. Fortunately, she had a large storehouse of badassery.

The fielder snagged the ball in shallow left and in one step fired a bullet toward home. It was gonna be a close play! Ryan’s scream from the stands could be heard all over the field, “Slide, Mom! Slide!” The catcher straddled the plate and caught the perfect throw chest-high. Robin slid between the catcher’s feet – the only open path to the plate. Dust flying! The crowd of maybe 40 people roaring! Before the catcher could apply a tag, the umpire hollered, “Safe!” with arms outstretched, palms down.

Robin got up, dusted herself off smiling, and trotted to the bench. Later, she asked, “What were you thinking? You KNOW I can’t run!” I could only answer, “Well, I didn’t know the left fielder had that kind of an arm.”

One thing I did know is that Robin always threw herself into anything she tackled. BA in Economics. Phi Beta Kappa. Law Degree. High level manager in the energy industry. Courtroom lawyer. Talented dancer, pianist (soloist with the Shreveport Symphony), and guitar player. Above all, a devoted Mom. But I am ahead of myself.

Most of her accomplishments were against the odds. Take that slide into home during a Houston City League softball game. She had never done that before, but it did not stop her trying and succeeding. In softball, runners cannot leave the base until the ball is hit. They cannot take a nice extended lead. A runner on second is NOT guaranteed to score on a single to the outfield. At five foot two and forty-two years old, Robin was probably the shortest and oldest infielder in the league. The catcher stood about five foot ten and weighed one eighty. There was no way Robin could go through that woman, so she slid under her. The catcher may have been bigger and quicker, but Robin was older and cagier – and more determined. There was only one way to make that play work, and Robin found it. Sorta characteristic of her life: faced with an obstacle, Robin usually found a way.

As a kid in Shreveport, Louisiana, she was always athletic. Climbing trees. Playing tag. To her parents’ credit, they encouraged this active behavior. They sent her to a summer camp where she excelled at all types of activities. Camp Fern in Marshall, Texas, was on a small lake where girls learned swimming, canoeing, and water skiing. There was always an element of competition both individually and against the other tribe. They also competed in horseback riding, riflery, and archery. Robin was never the biggest or the fastest but became a leader of one tribe. When she outgrew being a camper, she became a counselor’s aide and then a counselor. She was an instructor in water skiing and riflery – the first female counselor to drive the ski boat and run the rifle range. Over ten summers, Robin was challenged physically and recognized in competition against her peers.

As a student at The University of Oklahoma, she majored in Economics. She was an academic standout and an officer of her sorority. She landed the lead dance and singing role in a major student stage production.

A neighboring fraternity recognized her academic prowess and asked her help tutoring its members through a Statistics course. Stat was known as one of the flunk-out courses in the Business Department. Every one of her eight ”students” passed!

She left college before completing her degree to marry the luckiest man in the world and to start a family. Nevertheless, she resolved she was going to complete her education – somewhere – sometime. It didn’t take long. Three years later she graduated with honors from OU. She could not immediately put her degree to work because she was tied to the itinerant lifestyle of a military wife.

She created other outlets in lieu of gainful employment. She painted. She wrote poetry. She doted on her two sons. She spearheaded a crisis intervention Help Line. In her spare time, she wrote a subversive column for “Listen Ladies,” the Officers Wives Club newsletter. The column was unabashedly feminist, a radical position on a military base in the early 1970s. Importantly, she wrote well, with precision, with explicit expression, and with no wasted words. She is the only person I have ever met who can edit their own writing. This talent would not be wasted.

In 1973, her family became unshackled from the military, and she sought professional employment where she could put her Economics degree to work. Three questions common to her interviews loomed as obstacles, only one of which seemed legitimate. “Do you speak any computer language?” Fair enough. She did not, so she immediately enrolled in a Fortran class. “How many words per minute do you type?” Pardon me? I have an Econ degree. I am not applying for a secretarial position. And, finally, “What will you do with your children?” She wanted to say she would put them up for adoption, of course. What’s the answer to that question anyway? Love them? Cherish them? Help them reach their goals?

Several months later, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission announced an audit of a company that had declined to hire her. The company’s highest-ranking female at the time was an Executive Secretary. The company needed immediate progress in hiring females and minorities to avoid large fines. It scrambled through its files and found this previously rejected woman.

“Are you still interested in employment?” “Yes,” she answered, “and I now speak Fortran.” She was hired on the spot as an Analyst in the Economics and Planning Department.

Her second day on the job, she learned that the department taught Fortran to all incoming employees who were not computer literate. So much for that first interview question being a legitimate obstacle.

During her second month, the department hired a male college grad with no experience at twice her salary. The handwriting about sexist discrimination was chiseled into the wall, but she did not give up.

Her boss quickly recognized her intelligence, analytical skills and writing talents. He drafted her into a fledgling mergers and acquisitions group tasked with recommending steps to diversify this stodgy old pipeline company. Her efforts steered the company into some profitable ventures and away from risky ones. She graduated from analyzing and preparing material for executive review into presenting those materials to the board of directors. Her expertise grew to encompass the whole enterprise. She led the creation of an annual strategic plan for the company with periodic updates during the year.

All the while, she was a wonderful wife and mother, raising and nurturing two wonderful sons. To hear her tell it now, she regrets the long hours and some weekend work wishing she had spent more time with her boys. But if you ask them, they will tell you about her attendance at early Saturday morning soccer games in the dead of winter. They’ll mention her love of baseball and family tickets to Astros games. Annual summer vacations to The Other Place on the Comal River, including the time spent in a rickety cabin she christened “The Pit” during a thunderstorm. Drives around the Hill Country searching for “Mom’s Eats” or the best café the small towns offered. Finding Luckenbach and the Grist Mill at Gruene and Naeglin’s Bakery in New Braunfels.

Ski trips to Colorado. Vacations to Cozumel. Singing and playing the guitar at night to put both boys to sleep when they were toddlers. Playing piano accompaniment for Burke’s saxophone solo at University Interscholastic League competitions. Listening to old 45 rpm records with Ryan when he was interested in learning the guitar. And later, the midnight trips to Houston after attending his band’s performance at Hole in the Wall or other Austin venues. She helped make life an adventure for everyone around her. And her boys loved it.

Her career took a turn when the executive she had worked with for years departed the pipeline company and joined an independent oil and gas producer. The opportunity was there for the pipeline company to promote her into a higher role, but they blew it. Instead of promoting her, they asked her to assume an expanded role, but with no title or additional pay. As I said, the gender discrimination ran deep. Within a couple of months, her old boss called with an offer at the oil and gas company. She considered it for a while and accepted.

Her new company had no planning systems despite being deeply involved in overseas and domestic exploration and production. Her new job was to create that function from scratch, and then convince a bunch of crusty oil patch guys to buy into the program. She successfully developed systems that helped the company make good decisions. After seven years, she had had enough. One deciding factor? Again, gender discrimination. She observed to her boss that she performed functions and had responsibility equal to two male employees who were titled vice presidents. Her title? Director, a notch below vice president and one that existed nowhere else in the company. She suggested they should all have equal rank. The response of the company — you probably guessed — they demoted the two officers to directors!

She soon resigned and entered law school, fulfilling a dream from her earliest days in college. Before classes began, the law school informed her she had been granted a scholarship for which she had not even applied. Her first summer, she walked into the Houston office of the American Civil Liberties Union and asked if she could help. They immediately put her to (unpaid) work researching First Amendment issues related to an existing case. The next semester, the ACLU recognized her as volunteer of the year with a cash stipend. Law school was a great fit. She made Law Review, graduated with honors, and went to work for a respected firm as “the world’s oldest living associate,” as she laughingly said.

She became a civil litigator, standing up in court, thinking on her feet, and trying to find justice for her clients. After several years, the law firm dissolved as partners spun out into boutique firms or private practice. She followed suit and ran her own business until retiring.

Meanwhile, Burke’s wife was accepted to medical school. The couple planned to move their family south of Houston, a shorter drive to the Med Center. Without a moment’s delay, Robin said we needed to move into the same neighborhood to help with their three school-age children. Robin met the grandchildren at 6:30 each the morning when their mother dropped them at the bus stop and waited with them until the school bus arrived. She then took care of her law clients until meeting the school bus in the afternoon.

Robin loves gardening and genealogy. After retirement, she directed more energy toward those hobbies with a lush vegetable garden in the back yard and frequent road trips to county courthouses and archives in search of “dead relatives.” At the age of 66, she mentioned we had never been to the Houston Boat Show. A few days later we took delivery of a 17-foot tandem kayak. She also won a raffle for a thousand-dollar shopping spree for fishing gear. Our kayak soon had a trolling motor and a fish finder. We had fun exploring local lakes, rivers, and salt water fishing near San Luis Pass.

As age crept up on us, our retirement morphed. Most of our friends are now those from church rather than business associates. A swimming pool replaced the garden in a nod to our creaky knees. For similar reasons, the kayak gave way to a bigger boat. The genealogical road trips have decreased in number as more original documents became available online. And we have explored more foreign cities, Paris being our favorite. A dozen years later, she has survived ovarian cancer and is recovering from hip replacement surgery. Slide, Mom! Slide! We look forward to more fishing trips before selling the boat and moving to Austin to be closer to our boys. It is sure to be another adventure regardless of the obstacles.

Thank you, Robin Rankin Willis, the love of my life, my best friend, my wife, and my hero.

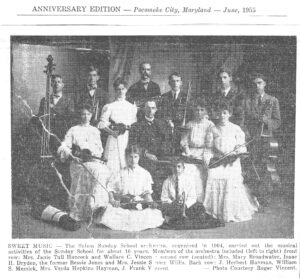

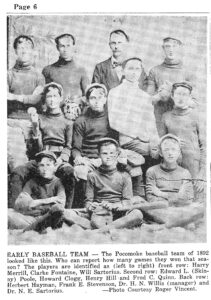

A photo of the group published in the local paper shows her seated at the far right. According to the paper, the ensemble organized in 1904 and played for about ten years.

A photo of the group published in the local paper shows her seated at the far right. According to the paper, the ensemble organized in 1904 and played for about ten years.

Some team members appear to be high school students, others young adults. This was typical of the era – think “Field of Dreams” – when towns fielded amateur teams for friendly competition.

Some team members appear to be high school students, others young adults. This was typical of the era – think “Field of Dreams” – when towns fielded amateur teams for friendly competition.

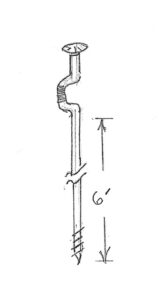

Her idea was to “drill down into some of the coffins to extract DNA.” Thus her nickname. She died not long thereafter, apparently not having succeeded with her DNA recovery project. If she had, any human DNA would undoubtedly have been mixed with pine tree DNA. Not sure if FTDNA could handle that.

Her idea was to “drill down into some of the coffins to extract DNA.” Thus her nickname. She died not long thereafter, apparently not having succeeded with her DNA recovery project. If she had, any human DNA would undoubtedly have been mixed with pine tree DNA. Not sure if FTDNA could handle that.